‘Beyond the Gift: The Art of Major Donor Stewardship’ Part 3.

Introduction

At Cairney & Company we work with so many different clients, whose donors are all unique and need to be managed with this in mind. The topic of good stewardship is a recurring one. How to do it well, treating each individual as such whilst maintaining an appropriate level of consistency in approach? It is a hugely important part of the donor journey, and it is crucial to get it right.

In parts one and two of this three-part blog series, we explored what stewardship actually is and why it is important as well as what makes good stewardship. This final blog of the series will focus on how your institution can stand out from the crowd and offer a point of difference in its major gift stewardship.

So…how do you stand out from the crowd when it comes to donor stewardship?

According to a 2015 study by Microsoft, the average attention span has decreased from twelve seconds in the year 2000 to a mere eight seconds at the time of their research (and bear in mind, that’s a year before TikTok was invented). To put that into some context, that is less than the nine-second attention span of your average goldfish.[i] To make matters worse, the average employee receives around 121 emails in a working day. [ii]Add that to the plethora of instant messenger apps that we have for work, and the fact that smartphones have allowed our personal and work lives to seep a little more into each other, and we are subject to a constant stream of information. So how on earth do you break through all that noise?

1 – make it personal

First and foremost, make it personal. Whatever medium you choose to communicate with your donors, the message should be specifically for them and not a ‘copied and pasted’ number that has been sent to all donors from the beginning of time. Echo their tone: if you are working with a donor who likes to share details of their personal life with you, then be sure to ask them about this when you’re in touch following the donation. If they mention their kids, be interested and remember the details for future conversations, just like you would when you meet someone outside of a work context. Similarly, if someone shows clearly that they prefer to take a business approach to their philanthropy, do not make them uncomfortable by asking questions about their private lives. Read the room.

Bespoke reports are a great way to steward donors, and it should not take too much to personalise them. Our Donor Relations team at UCL maintain a ‘Fundraiser Resource Bank’ on which to base the content for our proposals and reports, and then as fundraisers we can personalise this to suit each donor’s requirements. Think about which of the ‘seven faces’ fits them best and use this when creating your report. Remember to focus on what the donor wants to hear, not what you want to say.

Meet with your donor and update them yourself. Whilst there is no getting around the resource-intensity of it, this is often a great way to ensure continued support. Meeting with your donors in this context is a great way to hear first-hand from them how their experience as a donor has been. What have they enjoyed most? What would they like more of from the institution? Have they thought about whether this is something they might consider doing again? These are not questions you are likely to have answered by sending them a report. Broadcasting does not = good communication. It should be a two-way conversation; you have to provide a reason and a forum for people to engage with you, or else you have no idea if what you are doing is working.

That being said, despite the hugely positive vaccine role out, 2021 will likely continue to be uncertain and meetings ‘in real life’ are undoubtedly going to be few and far between. This looks set to continue for the foreseeable future. Zoom and Teams have taken over working life and have been helpful in ensuring we can still ‘meet’ with our donors, and our colleagues. Despite some of the obvious challenges, this technology does have its benefits. In some cases, it has made a slideshow fit much more naturally into a donor meeting. However, video-calling will not work for everyone. So do not forget to use the telephone! A phone call is such a personal, resource-light way to touch base with a donor and thank them for their support. In fact, at the beginning of lockdown, all those who gave to UCL’s Coronavirus Response Fund (who had opted in appropriately) received a personal thank you phone call. Similarly, a letter can be a really nice way to say thank you. Particularly a handwritten note can often have a huge personal impact, especially now.

2- A picture paints a thousand words

In a 1982 article in Business Week, Computer Pictures Corporation’s then-president Philip Cooper wrote: “people assimilate visual information about 60,000 times faster than they assimilate printed copy.” This statistic is used time and time again by marketers and journalist to prove the importance of the visual. Now, while it seems that this figure has absolutely no scientific basis at all, as well as no sources, the sentiment does ring true. According to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), ‘a striking characteristic of human memory is that pictures are remembered better than words.’[iii]

With attention in constant demand, being fought over by so many competing entities, we do not have much time in which to grab the attention of our audience. Complex, text heavy documents are less likely to catch the eye of our donors. In addition, it is not just our donors’ attention that is in short supply, it is also their time. The average person reads 200-250 words per minute, which is no faster than we did 100 years ago. A stewardship report has around 500 words per page, so we need to be conscious about how much time we demand from people when writing these reports.

When we are taught to read at school, we are introduced to the concept of ‘SKIM – SCAN – READ’.

Skimming

· Under 5 seconds

· Our eyes jump around, fixing on a maximum of around 10 points

· Our eyes focus on pictures, keywords, logos, words in bold, italics and subheadings.

Scanning

· Read the whole headline, more of the copy, the image and the captions.

Reading

· Read the full text.

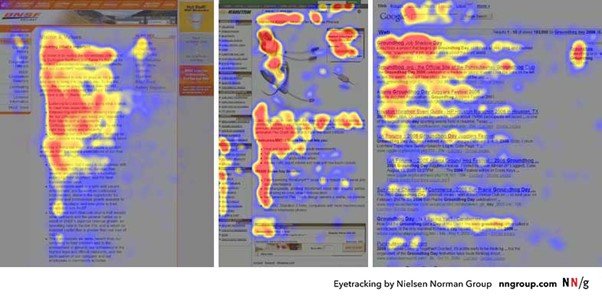

However, unlike in preparation for Comprehensive Literature exams, often people will skip the ‘reading’ part and just skim. Eye-tracking technology shows that people tend to read in an ‘F-shaped pattern’.[iv]

Our eyes focus on headlines, subtitles, images, captions and the first paragraph. So when it comes to reports, make sure to keep your messaging short and snappy to grab the attention of the reader. Always use white space appropriately and include photographs and diagrams.

For shorter updates, why not try a video update from an academic, scholarship student or institutional leader? This can be a great way to provide a personal update with no text-heavy documents. However, always make sure to include closed captions on all videos for those with hearing difficulties and for those who wish to watch the video without sound.

3- Money can’t buy experiences

A key component of stewardship in any institution is to create experiences that cannot be bought; that are unique. This type of experience ranges vastly from institution to institution depending on size, geography and budget.

One of the most commonly used tools in this regard is location. Unsurprisingly an event that’s hosted in an exclusive venue that is usually not open to the public is likely to be a big draw for donors. The target audience is less likely to be enticed by The Mandarin Oriental, which money can buy, and more likely to be attracted to an event held at the top of the Orbit in Stratford, which money cannot buy.

This target audience is also likely to be drawn in by the name on the ticket. An event that is ‘hosted by’ a member of institutional leadership, or a senior volunteer in the public eye, is much more likely to attract donors and provide them with a memorable experience.

However, a ‘money cannot buy’ experience is not synonymous with extravagance, expense and luxury. Human beings are fundamentally predisposed to storytelling and listening to stories. It is part of the very fabric of our being. Not only that, research shows that when a story resonates with us, our Oxytocin (a happy hormone) levels increase. This is one of the most powerful tools we have in making our donors see and feel the impact they have had - tell the story. A simple and key example of such an experience is providing an opportunity for a donor to meet their scholarship student. This is a low-cost and tangible way to showcase the impact of the donor’s support. Furthermore, research into storytelling shows that human beings find it easier to relate to an individual as opposed to a group. So, hearing the individual story of their scholarship recipient is one of the most effective ways to steward someone. Couple this with the bigger picture of positive impact within the storyline of one individual for maximum effect.

For example:

Scholarship student is funded to study medicine = big positive impact on one life

This student goes on to make a breakthrough in cancer research = impact on thousands of lives.

As this follows the story of one individual it is easy for the human brain to relate to, but it tricks the brain into taking in the bigger picture and shows the vast impact that an individual can have.

CONCLUSION

Stewardship is arguably the most important step in the donor journey. Not only do institutions owe it those who invest in their cause to thank them, but it also makes simple business sense. What makes good stewardship on the other hand is much more of a grey area and is different from donor to donor. Whilst profiling your donors can help to map this out, the best way to understand what is landing well with a donor and what is not, is to ask.

When it comes to standing out from all the noise of 21st century living, it is clearly harder than ever. However, key strategies stand the test of time: make it personal – this is about them as donors, not us as fundraisers; try to avoid text heavy documents – make it easy and enjoyable to read; provide experiences that money cannot buy. In other words – be memorable. Most important though is to communicate with our donors, to find out what they like to hear about and indeed what they do not. As with any relationship, in any area of our life, communication is the key to its success.

[i] Microsoft, 2015, Microsoft Attention Spans, Page 6

[ii] Campaign Monitor, 2019, Email Marketing.

[iii] Craik, Fergus I.M; Grady, L. Cheryl; McIntosh, Anthony R.; Rajah, Natasha M; PNAS; March 1998; Neural correlates of the episodic encoding of pictures and words

[iv] NN/g Nielsen Norman Group; April 2006; F Shaped Pattern For Reading Web Content.